Lateran calleth this priviledge granted unto Henry a praviledge, playing upon the word, condemnes it, casseth, and declares it a nullitie.

— Guillaume Ranchin, translated by Gerard Langbaine, Review of Councell of TrentI came of age in the midst of a long and messy conversation on privilege. And despite my own politics, I found so much of this conversation to be frustrating.

The trouble was not that I disagreed with the basic contentions of the so-called woke. It’s pretty clear that — in some very, very important ways — the rich have it easier than the poor, the healthy have it easier than the sick, the straight have it easier than the queer, men have it easier than women, whites have it easier than non-whites, and so on. Every honest and intelligent person I’ve ever known basically accepts these premises.

My issue was rarely with the function of the conversations, but with their form. If anything, my alignment with the fundamentals only heightened this frustration. I never let this frustration alienate me from my values, but it’s still hard to see your own beliefs so clumsily advanced.

I never liked the preamble. I didn’t like the convention of discourse insisting that each speaker should begin their contribution with a declaration and situation of their own identity. My issue with the practice was less that it was boring and cumbersome — although it was those things — and more with the fact that it misconstrued the nature of privilege. Attributes like class or gender or race are many things, but they are rarely unapparent. Privilege is legible — that’s the point of it.

I never liked how many questions were collapsed into one line of inquiry. Is privilege good or bad? Is a privilege good or bad? These are not the same question.

Let me give you two common examples of male privilege. First, a man can travel almost anywhere at any time without any fear. Second, a man who hurts a woman has a good chance of getting away with it. Is it helpful to call each of these a case of privilege?

In all those conversations, I never heard someone differentiate between those privileges we want everyone to have and those privileges we want no one to have. This failure to distinguish seemed so lazy to me. In a time when so many people were creating so many terms of analysis, no one bothered to coin that word.

In fact, this discernment wouldn’t require the creation of a new word but the exhumation of an old one. Middle English had the word pravilege — an inflection of the word privilege with the root prav (meaning “corruption” or “evil” or “wickedness”, as in depravity) — to mark “an evil, injurious, or worthless privilege”.

I didn’t need anyone to tell me the mob was going after my ability to hurt people — an ability I’m not interested in having — and not my ability to move freely. But I think some of my fellow men might have appreciated the distinction.

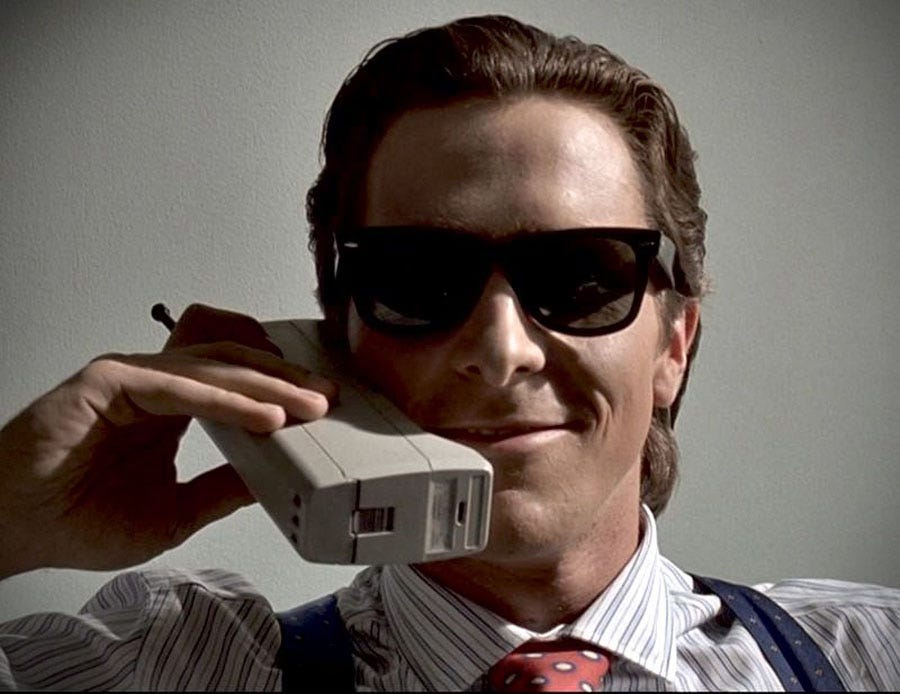

If you can forgive me, I’d like to share a piece of Nazi propaganda I came across at the end of last year. I don’t use that term lightly — the video below was shared by an avowed white nationalist, which is increasingly common on what was Twitter.

This is the kind of artifact that disorients you. The self-serious music. The sometimes silly headlines. The stock footage. The looming quotation. It’s hard for me to wrap my head around this as anything but a wonderful work of satire. But whoever shared this was — God help them — deadly serious.

It’s true that the Great American Reckoning had some duds. The conversation spawned all sorts of headlines, and some of them were pretty funny. I don’t think anyone would earnestly contest that.

I still remember how I experienced that moment in time. I still remember how other white boys experienced that moment in time. I still remember the wide, wide gap between the two.

The dumb men felt those headlines were an attack on their status. But the smart men knew those headlines to be a defense of the same. That’s how I remember it, anyways.

If those articles really were painting them — us — as some sort of all-powerful high priesthood of modern society, wouldn’t that make you feel, if anything, a little bolder?

When I saw other white boys complain about a national conversation reiterating their status, I remember feeling disoriented.

It was so hard to take them seriously, to not sneer at them a little. Heavy is the head that wears the crown. I guess some of us aren’t cut out for it.

I remember the first time I heard a real-life conservative pull that reverse racism card. He told me his son had gotten pulled over for “driving while white”. He went on to explain that his son had gotten “a bullshit speeding ticket”. I looked at the man like he was having a stroke. Your son — I wanted to tell him — is a young man in a fast car. He was obviously speeding. The same way you speed. The same way I speed. I don’t think I've ever met a man who’s never sped. It was bizarre to see an old man forfeit his knowledge of how young men act. And it was startling to see a man so terribly misunderstand his place in history. Here he was, after half a century at the top of the greatest apparatus since the Roman Empire, groveling about a speeding ticket. It was as if he had squandered the great power he was born into.

In recent years, conservative women have begun asking me what it’s like to be a man. They broach the question in the same hushed tones liberals used to bother their Black coworkers. What’s it like to be a white man these days?

Well, it fucking rocks.

It’s like hitting every green light on a crosstown drive — that’s what it’s like to be a white boy.

Every time you meet someone new, you get to meet the best version of them. People are trusting and helpful and friendly and courteous and kind. You never feel scared and never feel scary. People look for the best in you. They give you second chances.

They give you third and fourth and fifth chances, too. Even if someone is wary of white boys — and many people have good reason to be — they tend to relax pretty quickly.

Somehow, something about you always reminds a stranger of someone they like. You move through the world as a man — yes — but also as a friend or a brother or a son.

It’s rare that your trust is betrayed. And it’s very rare that such miscalculations have any real consequence. All this lets you look for the best in people.

At a very early age, you learn you can get away with almost anything. The only trick is to get away with the right things for the right reasons.

Things almost always work out for you.

It’s like magic.

In just this one sense, I have some respect for all those frat boys I knew at Ole Miss. Some of them had abhorrent personalities. Many of them had abhorrent politics. But all of them knew how good they had it. I never once heard any of them whining about how hard it is to be a white man. Each of them — if you let them be honest with you — would admit that he’d been born into what is essentially an unshakable aristocracy. And each of them — if you made them be honest with you — would explain that aristocracy is very far from “rule by the best”. Those boys knew their lives to be easy.

It’s for this reason that I have no pity for the manosphere, for the men’s rights activists, for the men going their own way, for the pick-up artists, for those who have taken the red pill, for those who have taken the black pill, for the incels and the doomers, for the traditionalists and the patriarchs, for the high-value men. I have no pity for any man who sincerely believes himself to be oppressed by women. I loathe men who talk like this. I look at them like filth. It’s not just that this way of thinking is evil or false or harmful. It’s that it’s embarrassing.

Feminists should be fighting the draft. . . . Marriage is a legal trap. . . . The trick is to play with her emotions. . . . She should be chasing your validation. . . . No amount of self-improvement will make up for bad genetics. . . . Modern feminism has destroyed the family. . . . Women don’t want love . . . .

If my son ever talked like this, I would kill him on the spot.

Of course, plenty of those frat boys were misogynists. In fact, a lot of what bonded them together was a particular kind of misogyny. But none of them was a self-pitying misogynist. And none of them would pretend — even for a moment — that women had it better than they did. Each of them knew that he was one very easy college degree away from — at worst — an ill-gotten and well-paid career at the chain of regional banks managed by his uncle. He would have a beautiful wife and a big house with lots of new cars in the driveway. He’d play golf at a nice country club and his daughter would play soccer for her segregation academy. That much was all but guaranteed to him as birthright. His only task was to not fuck up too badly.

The ethos of the SEC frat scene is to flaunt this privilege and — in doing so — to foster it. Their honesty about their place in the hierarchy of the Mid-South is somewhat disarming and somehow charming. The boys I knew rarely fell for — and often rejected — the self-pitying grievance politics becoming popular among other young men. In junior year, a friend of mine showed me a video of Jordan Peterson whining about how hard it is to be a straight man these days. If I said this shit at the house, my friend said, someone would press a lit cigarette to the back of my neck.

It’s hard for me to disentangle these lessons — if they are indeed lessons — from the time and place that gave them to me. It was no small thing to live through the year 2020. But to live through it in the Deep South was something else entirely.

It was in Mississippi that I first met people born into such extreme poverty — such profound destitution — that each had nothing to lose and everything to gain. It’s a grave injustice that people are born into and bound up in such hopelessness. It’s also a fatal error for any society. There’s a reason that the poorest places have the highest murder rates.

It was in Mississippi that I first met people born into such startling privilege — or, rather, pravilege — that almost no misstep could truly afflict them. No one flourishes in an aristocracy, not even the aristocrats. I remember trying to explain this to a crowd of strangers.

This was just a few weeks after we learned some of my classmates had posed for a photograph, heavily armed, beside Emmet Till’s desecrated memorial. The university had sat on the image for months, shielding the boys — the young men — from shame.

I remember stumbling through my points. It’s a terrible thing for someone to be so immune to disaster, so insulated from consequence. It’s a terrible thing for someone to be so completely suspended from all effect. Some inversion of Tantalus. I remember shrugging to the crowd: We owe justice to perpetrators, too.

There are some powers everyone should have. There are some powers no one should have. A human being must at once enjoy some protected rights and endure some enforced obligations. But there are some things that lie between these extremes.

Everyone must have powers to lose. And everyone must be able to lose those powers.

Those powers can’t be conscience or dignity or those other things we hold to be inalienable. Those powers can’t be what we call rights. Those powers must be other things entirely — states of fame, degrees of fortune, kinds of freedom. Those powers, taken together, must be something like privilege. Within some bounds, people must be free to better or worsen their lives. Otherwise, things fall apart.

This is what so many people missed in that long and messy conversation about privilege. A society of unjust privilege is an unjust society. But a society without privilege is no society at all. No one can live without some way to rise, to risk, to fall. No one can lie beyond reach. No one can be left behind.

Brave writing. Thank you.

Really enjoyed this one. You always make me think!